Modern science

With the scientific revolution, paradigms established in the time of classical antiquity were replaced with those of scientists like Nicolaus Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Christiaan Huygens and Isaac Newton. During the 19th century, the practice of science became professionalized and institutionalized in ways that continued through the 20th century. As the role of scientific knowledge grew in society, it became incorporated with many aspects of the functioning of nation-states.

Natural sciencesedit

Physicsedit

The scientific revolution is a convenient boundary between ancient thought and classical physics. Nicolaus Copernicus revived the heliocentric model of the solar system described by Aristarchus of Samos. This was followed by the first known model of planetary motion given by Johannes Kepler in the early 17th century, which proposed that the planets follow elliptical orbits, with the Sun at one focus of the ellipse. Galileo ("Father of Modern Physics") also made use of experiments to validate physical theories, a key element of the scientific method. Christiaan Huygens derived the centripetal and centrifugal forces and was the first to transfer mathematical inquiry to describe unobservable physical phenomena. William Gilbert did some of the earliest experiments with electricity and magnetism, establishing that the Earth itself is magnetic.

In 1687, Isaac Newton published the Principia Mathematica, detailing two comprehensive and successful physical theories: Newton's laws of motion, which led to classical mechanics; and Newton's law of universal gravitation, which describes the fundamental force of gravity.

During the late 18th and early 19th century, the behavior of electricity and magnetism was studied by Luigi Galvani, Giovanni Aldini, Alessandro Volta, Michael Faraday, Georg Ohm, and others. These studies led to the unification of the two phenomena into a single theory of electromagnetism, by James Clerk Maxwell (known as Maxwell's equations).

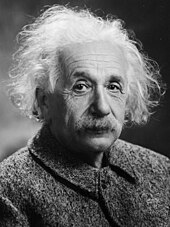

The beginning of the 20th century brought the start of a revolution in physics. The long-held theories of Newton were shown not to be correct in all circumstances. Beginning in 1900, Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr and others developed quantum theories to explain various anomalous experimental results, by introducing discrete energy levels. Not only did quantum mechanics show that the laws of motion did not hold on small scales, but the theory of general relativity, proposed by Einstein in 1915, showed that the fixed background of spacetime, on which both Newtonian mechanics and special relativity depended, could not exist. In 1925, Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger formulated quantum mechanics, which explained the preceding quantum theories. The observation by Edwin Hubble in 1929 that the speed at which galaxies recede positively correlates with their distance, led to the understanding that the universe is expanding, and the formulation of the Big Bang theory by Georges Lemaître.

In 1938 Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann discovered nuclear fission with radiochemical methods, and in 1939 Lise Meitner and Otto Robert Frisch wrote the first theoretical interpretation of the fission process, which was later improved by Niels Bohr and John A. Wheeler. Further developments took place during World War II, which led to the practical application of radar and the development and use of the atomic bomb. Around this time, Chien-Shiung Wu was recruited by the Manhattan Project to help develop a process for separating uranium metal into U-235 and U-238 isotopes by Gaseous diffusion. She was an expert experimentalist in beta decay and weak interaction physics. Wu designed an experiment (see Wu experiment) that enabled theoretical physicists Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang to disprove the law of parity experimentally, winning them a Nobel Prize in 1957.

Though the process had begun with the invention of the cyclotron by Ernest O. Lawrence in the 1930s, physics in the postwar period entered into a phase of what historians have called "Big Science", requiring massive machines, budgets, and laboratories in order to test their theories and move into new frontiers. The primary patron of physics became state governments, who recognized that the support of "basic" research could often lead to technologies useful to both military and industrial applications.

Currently, general relativity and quantum mechanics are inconsistent with each other, and efforts are underway to unify the two.

Chemistryedit

Modern chemistry emerged from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries through the material practices and theories promoted by alchemy, medicine, manufacturing and mining. A decisive moment came when "chemistry" was distinguished from alchemy by Robert Boyle in his work The Sceptical Chymist, in 1661; although the alchemical tradition continued for some time after his work. Other important steps included the gravimetric experimental practices of medical chemists like William Cullen, Joseph Black, Torbern Bergman and Pierre Macquer and through the work of Antoine Lavoisier ("father of modern chemistry") on oxygen and the law of conservation of mass, which refuted phlogiston theory. The theory that all matter is made of atoms, which are the smallest constituents of matter that cannot be broken down without losing the basic chemical and physical properties of that matter, was provided by John Dalton in 1803, although the question took a hundred years to settle as proven. Dalton also formulated the law of mass relationships. In 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev composed his periodic table of elements on the basis of Dalton's discoveries.

The synthesis of urea by Friedrich Wöhler opened a new research field, organic chemistry, and by the end of the 19th century, scientists were able to synthesize hundreds of organic compounds. The later part of the 19th century saw the exploitation of the Earth's petrochemicals, after the exhaustion of the oil supply from whaling. By the 20th century, systematic production of refined materials provided a ready supply of products which provided not only energy, but also synthetic materials for clothing, medicine, and everyday disposable resources. Application of the techniques of organic chemistry to living organisms resulted in physiological chemistry, the precursor to biochemistry. The 20th century also saw the integration of physics and chemistry, with chemical properties explained as the result of the electronic structure of the atom. Linus Pauling's book on The Nature of the Chemical Bond used the principles of quantum mechanics to deduce bond angles in ever-more complicated molecules. Pauling's work culminated in the physical modelling of DNA, the secret of life (in the words of Francis Crick, 1953). In the same year, the Miller–Urey experiment demonstrated in a simulation of primordial processes, that basic constituents of proteins, simple amino acids, could themselves be built up from simpler molecules.

Earth Scienceedit

Geology existed as a cloud of isolated, disconnected ideas about rocks, minerals, and landforms long before it became a coherent science. Theophrastus' work on rocks, Peri lithōn, remained authoritative for millennia: its interpretation of fossils was not overturned until after the Scientific Revolution. Chinese polymath Shen Kua (1031–1095) first formulated hypotheses for the process of land formation. Based on his observation of fossils in a geological stratum in a mountain hundreds of miles from the ocean, he deduced that the land was formed by erosion of the mountains and by deposition of silt.

Geology did not undergo systematic restructuring during the Scientific Revolution, but individual theorists made important contributions. Robert Hooke, for example, formulated a theory of earthquakes, and Nicholas Steno developed the theory of superposition and argued that fossils were the remains of once-living creatures. Beginning with Thomas Burnet's Sacred Theory of the Earth in 1681, natural philosophers began to explore the idea that the Earth had changed over time. Burnet and his contemporaries interpreted Earth's past in terms of events described in the Bible, but their work laid the intellectual foundations for secular interpretations of Earth history.

Modern geology, like modern chemistry, gradually evolved during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Benoît de Maillet and the Comte de Buffon saw the Earth as much older than the 6,000 years envisioned by biblical scholars. Jean-Étienne Guettard and Nicolas Desmarest hiked central France and recorded their observations on some of the first geological maps. Aided by chemical experimentation, naturalists such as Scotland's John Walker, Sweden's Torbern Bergman, and Germany's Abraham Werner created comprehensive classification systems for rocks and minerals—a collective achievement that transformed geology into a cutting edge field by the end of the eighteenth century. These early geologists also proposed a generalized interpretations of Earth history that led James Hutton, Georges Cuvier and Alexandre Brongniart, following in the steps of Steno, to argue that layers of rock could be dated by the fossils they contained: a principle first applied to the geology of the Paris Basin. The use of index fossils became a powerful tool for making geological maps, because it allowed geologists to correlate the rocks in one locality with those of similar age in other, distant localities. Over the first half of the 19th century, geologists such as Charles Lyell, Adam Sedgwick, and Roderick Murchison applied the new technique to rocks throughout Europe and eastern North America, setting the stage for more detailed, government-funded mapping projects in later decades.

Midway through the 19th century, the focus of geology shifted from description and classification to attempts to understand how the surface of the Earth had changed. The first comprehensive theories of mountain building were proposed during this period, as were the first modern theories of earthquakes and volcanoes. Louis Agassiz and others established the reality of continent-covering ice ages, and "fluvialists" like Andrew Crombie Ramsay argued that river valleys were formed, over millions of years by the rivers that flow through them. After the discovery of radioactivity, radiometric dating methods were developed, starting in the 20th century. Alfred Wegener's theory of "continental drift" was widely dismissed when he proposed it in the 1910s, but new data gathered in the 1950s and 1960s led to the theory of plate tectonics, which provided a plausible mechanism for it. Plate tectonics also provided a unified explanation for a wide range of seemingly unrelated geological phenomena. Since 1970 it has served as the unifying principle in geology.

Geologists' embrace of plate tectonics became part of a broadening of the field from a study of rocks into a study of the Earth as a planet. Other elements of this transformation include: geophysical studies of the interior of the Earth, the grouping of geology with meteorology and oceanography as one of the "earth sciences", and comparisons of Earth and the solar system's other rocky planets.

Environmental science is an interdisciplinary field. It draws upon the disciplines of biology, chemistry, earth sciences, ecology, geography, mathematics, and physics.

Astronomyedit

Aristarchus of Samos published work on how to determine the sizes and distances of the Sun and the Moon, and Eratosthenes used this work to figure the size of the Earth. Hipparchus later discovered the precession of the Earth.

Advances in astronomy and in optical systems in the 19th century resulted in the first observation of an asteroid (1 Ceres) in 1801, and the discovery of Neptune in 1846.

In 1925, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin determined that stars were composed mostly of hydrogen and helium. She was dissuaded by astronomer Henry Norris Russell from publishing this finding in her Ph.D.thesis because of the widely held belief that stars had the same composition as the Earth. However, four years later, in 1929, Henry Norris Russell came to the same conclusion through different reasoning and the discovery was eventually accepted.

George Gamow, Ralph Alpher, and Robert Herman had calculated that there should be evidence for a Big Bang in the background temperature of the universe. In 1964, Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson discovered a 3 Kelvin background hiss in their Bell Labs radiotelescope (the Holmdel Horn Antenna), which was evidence for this hypothesis, and formed the basis for a number of results that helped determine the age of the universe.

Supernova SN1987A was observed by astronomers on Earth both visually, and in a triumph for neutrino astronomy, by the solar neutrino detectors at Kamiokande. But the solar neutrino flux was a fraction of its theoretically expected value. This discrepancy forced a change in some values in the standard model for particle physics.

Biology and medicineedit

William Harvey published De Motu Cordis in 1628, which revealed his conclusions based on his extensive studies of vertebrate circulatory systems. He identified the central role of the heart, arteries, and veins in producing blood movement in a circuit, and failed to find any confirmation of Galen's pre-existing notions of heating and cooling functions. The history of early modern biology and medicine is often told through the search for the seat of the soul. Galen in his descriptions of his foundational work in medicine presents the distinctions between arteries, veins, and nerves using the vocabulary of the soul.

In 1847, Hungarian physician Ignác Fülöp Semmelweis dramatically reduced the occurrency of puerperal fever by simply requiring physicians to wash their hands before attending to women in childbirth. This discovery predated the germ theory of disease. However, Semmelweis' findings were not appreciated by his contemporaries and handwashing came into use only with discoveries by British surgeon Joseph Lister, who in 1865 proved the principles of antisepsis. Lister's work was based on the important findings by French biologist Louis Pasteur. Pasteur was able to link microorganisms with disease, revolutionizing medicine. He also devised one of the most important methods in preventive medicine, when in 1880 he produced a vaccine against rabies. Pasteur invented the process of pasteurization, to help prevent the spread of disease through milk and other foods.

Perhaps the most prominent, controversial and far-reaching theory in all of science has been the theory of evolution by natural selection put forward by the English naturalist Charles Darwin in his book On the Origin of Species in 1859. He proposed that the features of all living things, including humans, were shaped by natural processes over long periods of time. The theory of evolution in its current form affects almost all areas of biology. Implications of evolution on fields outside of pure science have led to both opposition and support from different parts of society, and profoundly influenced the popular understanding of "man's place in the universe". In the early 20th century, the study of heredity became a major investigation after the rediscovery in 1900 of the laws of inheritance developed by the Moravian monk Gregor Mendel in 1866. Mendel's laws provided the beginnings of the study of genetics, which became a major field of research for both scientific and industrial research. By 1953, James D. Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins clarified the basic structure of DNA, the genetic material for expressing life in all its forms. In the late 20th century, the possibilities of genetic engineering became practical for the first time, and a massive international effort began in 1990 to map out an entire human genome (the Human Genome Project).

The discipline of ecology typically traces its origin to the synthesis of Darwinian evolution and Humboldtian biogeography, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Equally important in the rise of ecology, however, were microbiology and soil science—particularly the cycle of life concept, prominent in the work Louis Pasteur and Ferdinand Cohn. The word ecology was coined by Ernst Haeckel, whose particularly holistic view of nature in general (and Darwin's theory in particular) was important in the spread of ecological thinking. In the 1930s, Arthur Tansley and others began developing the field of ecosystem ecology, which combined experimental soil science with physiological concepts of energy and the techniques of field biology.

Neuroscience is a multidisciplinary branch of science that combines physiology, neuroanatomy, molecular biology, developmental biology, cytology, mathematical modeling and psychology to understand the fundamental and emergent properties of neurons, glia, nervous systems and neural circuits.

Social sciencesedit

Successful use of the scientific method in the natural sciences led to the same methodology being adapted to better understand the many fields of human endeavor. From this effort the social sciences have been developed.

Political scienceedit

Political science is a late arrival in terms of social sciences. However, the discipline has a clear set of antecedents such as moral philosophy, political philosophy, political economy, history, and other fields concerned with normative determinations of what ought to be and with deducing the characteristics and functions of the ideal form of government. The roots of politics are in prehistory. In each historic period and in almost every geographic area, we can find someone studying politics and increasing political understanding.

In Western culture, the study of politics is first found in Ancient Greece. The antecedents of European politics trace their roots back even earlier than Plato and Aristotle, particularly in the works of Homer, Hesiod, Thucydides, Xenophon, and Euripides. Later, Plato analyzed political systems, abstracted their analysis from more literary- and history- oriented studies and applied an approach we would understand as closer to philosophy. Similarly, Aristotle built upon Plato's analysis to include historical empirical evidence in his analysis.

An ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy and military strategy by Kautilya and Viṣhṇugupta, who are traditionally identified with Chāṇakya (c. 350–283 BCE). In this treatise, the behaviors and relationships of the people, the King, the State, the Government Superintendents, Courtiers, Enemies, Invaders, and Corporations are analysed and documented. Roger Boesche describes the Arthaśāstra as "a book of political realism, a book analysing how the political world does work and not very often stating how it ought to work, a book that frequently discloses to a king what calculating and sometimes brutal measures he must carry out to preserve the state and the common good."

During the rule of Rome, famous historians such as Polybius, Livy and Plutarch documented the rise of the Roman Republic, and the organization and histories of other nations, while statesmen like Julius Caesar, Cicero and others provided us with examples of the politics of the republic and Rome's empire and wars. The study of politics during this age was oriented toward understanding history, understanding methods of governing, and describing the operation of governments.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, there arose a more diffuse arena for political studies. The rise of monotheism and, particularly for the Western tradition, Christianity, brought to light a new space for politics and political action.citation needed During the Middle Ages, the study of politics was widespread in the churches and courts. Works such as Augustine of Hippo's The City of God synthesized current philosophies and political traditions with those of Christianity, redefining the borders between what was religious and what was political. Most of the political questions surrounding the relationship between Church and State were clarified and contested in this period.

In the Middle East and later other Islamic areas, works such as the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Epic of Kings by Ferdowsi provided evidence of political analysis, while the Islamic Aristotelians such as Avicenna and later Maimonides and Averroes, continued Aristotle's tradition of analysis and empiricism, writing commentaries on Aristotle's works.

During the Italian Renaissance, Niccolò Machiavelli established the emphasis of modern political science on direct empirical observation of political institutions and actors. Later, the expansion of the scientific paradigm during the Enlightenment further pushed the study of politics beyond normative determinations.citation needed In particular, the study of statistics, to study the subjects of the state, has been applied to polling and voting.

In the 20th century, the study of ideology, behaviouralism and international relations led to a multitude of 'pol-sci' subdisciplines including rational choice theory, voting theory, game theory (also used in economics), psephology, political geography/geopolitics, political psychology/political sociology, political economy, policy analysis, public administration, comparative political analysis and peace studies/conflict analysis.

Geographyedit

The history of geography includes many histories of geography which have differed over time and between different cultural and political groups. In more recent developments, geography has become a distinct academic discipline. 'Geography' derives from the Greek γεωγραφία – geographia, a literal translation of which would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes (276–194 BC). However, there is evidence for recognizable practices of geography, such as cartography (or map-making) prior to the use of the term geography.

Linguisticsedit

Historical linguistics emerged as an independent field of study at the end of the 18th century. Sir William Jones proposed that Sanskrit, Persian, Greek, Latin, Gothic, and Celtic languages all shared a common base. After Jones, an effort to catalog all languages of the world was made throughout the 19th century and into the 20th century. Publication of Ferdinand de Saussure's Cours de linguistique générale created the development of descriptive linguistics. Descriptive linguistics, and the related structuralism movement caused linguistics to focus on how language changes over time, instead of just describing the differences between languages. Noam Chomsky further diversified linguistics with the development of generative linguistics in the 1950s. His effort is based upon a mathematical model of language that allows for the description and prediction of valid syntax. Additional specialties such as sociolinguistics, cognitive linguistics, and computational linguistics have emerged from collaboration between linguistics and other disciplines.

Economicsedit

The basis for classical economics forms Adam Smith's An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. Smith criticized mercantilism, advocating a system of free trade with division of labour. He postulated an "invisible hand" that regulated economic systems made up of actors guided only by self-interest. Karl Marx developed an alternative economic theory, called Marxian economics. Marxian economics is based on the labor theory of value and assumes the value of good to be based on the amount of labor required to produce it. Under this assumption, capitalism was based on employers not paying the full value of workers labor to create profit. The Austrian School responded to Marxian economics by viewing entrepreneurship as driving force of economic development. This replaced the labor theory of value by a system of supply and demand.

In the 1920s, John Maynard Keynes prompted a division between microeconomics and macroeconomics. Under Keynesian economics macroeconomic trends can overwhelm economic choices made by individuals. Governments should promote aggregate demand for goods as a means to encourage economic expansion. Following World War II, Milton Friedman created the concept of monetarism. Monetarism focuses on using the supply and demand of money as a method for controlling economic activity. In the 1970s, monetarism has adapted into supply-side economics which advocates reducing taxes as a means to increase the amount of money available for economic expansion.

Other modern schools of economic thought are New Classical economics and New Keynesian economics. New Classical economics was developed in the 1970s, emphasizing solid microeconomics as the basis for macroeconomic growth. New Keynesian economics was created partially in response to New Classical economics, and deals with how inefficiencies in the market create a need for control by a central bank or government.

The above "history of economics" reflects modern economic textbooks and this means that the last stage of a science is represented as the culmination of its history (Kuhn, 1962). The "invisible hand" mentioned in a lost page in the middle of a chapter in the middle of the "Wealth of Nations", 1776, advances as Smith's central message.clarification needed It is played down that this "invisible hand" acts only "frequently" and that it is "no part of his the individual's intentions" because competition leads to lower prices by imitating "his" invention. That this "invisible hand" prefers "the support of domestic to foreign industry" is cleansed—often without indication that part of the citation is truncated. The opening passage of the "Wealth" containing Smith's message is never mentioned as it cannot be integrated into modern theory: "Wealth" depends on the division of labour which changes with market volume and on the proportion of productive to Unproductive labor.

Psychologyedit

The end of the 19th century marks the start of psychology as a scientific enterprise. The year 1879 is commonly seen as the start of psychology as an independent field of study. In that year Wilhelm Wundt founded the first laboratory dedicated exclusively to psychological research (in Leipzig). Other important early contributors to the field include Hermann Ebbinghaus (a pioneer in memory studies), Ivan Pavlov (who discovered classical conditioning), William James, and Sigmund Freud. Freud's influence has been enormous, though more as cultural icon than a force in scientific psychology.

The 20th century saw a rejection of Freud's theories as being too unscientific, and a reaction against Edward Titchener's atomistic approach of the mind. This led to the formulation of behaviorism by John B. Watson, which was popularized by B.F. Skinner. Behaviorism proposed epistemologically limiting psychological study to overt behavior, since that could be reliably measured. Scientific knowledge of the "mind" was considered too metaphysical, hence impossible to achieve.

The final decades of the 20th century have seen the rise of a new interdisciplinary approach to studying human psychology, known collectively as cognitive science. Cognitive science again considers the mind as a subject for investigation, using the tools of psychology, linguistics, computer science, philosophy, and neurobiology. New methods of visualizing the activity of the brain, such as PET scans and CAT scans, began to exert their influence as well, leading some researchers to investigate the mind by investigating the brain, rather than cognition. These new forms of investigation assume that a wide understanding of the human mind is possible, and that such an understanding may be applied to other research domains, such as artificial intelligence.

Sociologyedit

Ibn Khaldun can be regarded as the earliest scientific systematic sociologist. The modern sociology emerged in the early 19th century as the academic response to the modernization of the world. Among many early sociologists (e.g., Émile Durkheim), the aim of sociology was in structuralism, understanding the cohesion of social groups, and developing an "antidote" to social disintegration. Max Weber was concerned with the modernization of society through the concept of rationalization, which he believed would trap individuals in an "iron cage" of rational thought. Some sociologists, including Georg Simmel and W. E. B. Du Bois, utilized more microsociological, qualitative analyses. This microlevel approach played an important role in American sociology, with the theories of George Herbert Mead and his student Herbert Blumer resulting in the creation of the symbolic interactionism approach to sociology.

In particular, just Auguste Comte, illustrated with his work the transition from a theological to a metaphysical stage and, from this, to a positive stage. Comte took care of the classification of the sciences as well as a transit of humanity towards a situation of progress attributable to a re-examination of nature according to the affirmation of 'sociality' as the basis of the scientifically interpreted society.

American sociology in the 1940s and 1950s was dominated largely by Talcott Parsons, who argued that aspects of society that promoted structural integration were therefore "functional". This structural functionalism approach was questioned in the 1960s, when sociologists came to see this approach as merely a justification for inequalities present in the status quo. In reaction, conflict theory was developed, which was based in part on the philosophies of Karl Marx. Conflict theorists saw society as an arena in which different groups compete for control over resources. Symbolic interactionism also came to be regarded as central to sociological thinking. Erving Goffman saw social interactions as a stage performance, with individuals preparing "backstage" and attempting to control their audience through impression management. While these theories are currently prominent in sociological thought, other approaches exist, including feminist theory, post-structuralism, rational choice theory, and postmodernism.

Archaeologyedit

The development of the field of archaeology has it roots with history and with those who were interested in the past, such as kings and queens who wanted to show past glories of their respective nations. The 5th-century-BCE Greek historian Herodotus was the first scholar to systematically study the past and perhaps the first to examine artifacts. In the Song Empire (960–1279) of Imperial China, Chinese scholar-officials unearthed, studied, and cataloged ancient artifacts. The 15th and 16th centuries saw the rise of antiquarians in Renaissance Europe who were interested in the collection of artifacts. The antiquarian movement shifted into nationalism as personal collections turned into national museums. It evolved into a much more systematic discipline in the late 19th century and became a widely used tool for historical and anthropological research in the 20th century. During this time there were also significant advances in the technology used in the field.

The OED first cites "archaeologist" from 1824; this soon took over as the usual term for one major branch of antiquarian activity. "Archaeology", from 1607 onwards, initially meant what we would call "ancient history" generally, with the narrower modern sense first seen in 1837.

Anthropologyedit

Anthropology can best be understood as an outgrowth of the Age of Enlightenment. It was during this period that Europeans attempted systematically to study human behaviour. Traditions of jurisprudence, history, philology and sociology developed during this time and informed the development of the social sciences of which anthropology was a part.

At the same time, the romantic reaction to the Enlightenment produced thinkers such as Johann Gottfried Herder and later Wilhelm Dilthey whose work formed the basis for the culture concept which is central to the discipline. Traditionally, much of the history of the subject was based on colonial encounters between Western Europe and the rest of the world, and much of 18th- and 19th-century anthropology is now classed as scientific racism.

During the late 19th century, battles over the "study of man" took place between those of an "anthropological" persuasion (relying on anthropometrical techniques) and those of an "ethnological" persuasion (looking at cultures and traditions), and these distinctions became part of the later divide between physical anthropology and cultural anthropology, the latter ushered in by the students of Franz Boas.

In the mid-20th century, much of the methodologies of earlier anthropological and ethnographical study were reevaluated with an eye towards research ethics, while at the same time the scope of investigation has broadened far beyond the traditional study of "primitive cultures" (scientific practice itself is often an arena of anthropological study).

The emergence of paleoanthropology, a scientific discipline which draws on the methodologies of paleontology, physical anthropology and ethology, among other disciplines, and increasing in scope and momentum from the mid-20th century, continues to yield further insights into human origins, evolution, genetic and cultural heritage, and perspectives on the contemporary human predicament as well.

Emerging disciplinesedit

During the 20th century, a number of interdisciplinary scientific fields have emerged. Examples include:

Communication studies combines animal communication, information theory, marketing, public relations, telecommunications and other forms of communication.

Computer science, built upon a foundation of theoretical linguistics, discrete mathematics, and electrical engineering, studies the nature and limits of computation. Subfields include computability, computational complexity, database design, computer networking, artificial intelligence, and the design of computer hardware. One area in which advances in computing have contributed to more general scientific development is by facilitating large-scale archiving of scientific data. Contemporary computer science typically distinguishes itself by emphasising mathematical 'theory' in contrast to the practical emphasis of software engineering.

Materials science has its roots in metallurgy, mineralogy, and crystallography. It combines chemistry, physics, and several engineering disciplines. The field studies metals, ceramics, glass, plastics, semiconductors, and composite materials.

Metascience (also known as meta-research) is the use of scientific methodology to study science itself. Metascience seeks to increase the quality of research while reducing waste. The replication crisis is the result of metascientific research.

Comments

Post a Comment